Proceedings of the 29th Meeting

Working Group on Prolamin Analysis

and Toxicity (PWG)

Edited by Peter Koehler

German Research Centre for Food Chemistry, Freising

Verlag Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Lebensmittelchemie - 2016

Preface

The Austrian City of Tulln was the venue of the 29th meeting of the Working Group on Prolamin Analysis and Toxicity from 8 to 10 October 2015. The meeting was hosted

by Romer Labs Division Holding GmbH, and the Austrian Coeliac Society assisted in

the registration of the participants. Simone Schreiter, the local organiser, was present

during the entire meeting. More than 60 persons participated in the meeting. This

shows the ongoing scientific significance of the topic gluten and gluten

hypersensitivities. From the 12 current members of the PWG, nine participated in the

meeting. Peter Koehler, chairman of the PWG, welcomed the group, one invited

speaker, participants from industry, research institutes as well as delegates from

European coeliac associations. Industry delegates came from starch producers,

manufacturers of gluten-free foods, and producers of analytical test kits for gluten

quantitation.

Analytical and clinical work in the field of coeliac disease and gluten done in the labs

of the PWG members as well as results of guest speakers were presented in 15 talks

and intensely discussed at the meeting. In addition, two presentations addressed

regulatory aspects of gluten analysis and labelling. A symposium on “Innate Immunity

and Coeliac Disease” with three presentations of internationally recognized experts

highlighted the latest advances in the field of the early steps of CD pathogenesis and

non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity.

At this occasion, I would like to express my thanks to all participants for their active

contributions and to all persons that made the meeting possible. I would like to thank

the local organizing team, in particular Simone Schreiter of Romer Labs and also

Christian Petz and Hertha Deutsch of the Austrian Coeliac Society, who perfectly

organized the hotel, the venue, and the registration. Also, very special thanks go to

Katharina Scherf for her help in proofreading. Finally, I would like to express my

appreciation to all friends, colleagues and sponsors for their ongoing support of the

PWG and the meeting.

Freising, March, 2016 Peter Koehler

1. Executive Summary

Among the topics of the meeting were analytical issues of gluten, novel approaches for

coeliac disease diagnosis, aspects of the innate and adaptive immune response, as well

as legal issues and standardization activities.

Analytical session

Six presentations were given in this session. The opening lecture and an additional talk

within the session discussed the requirements and current activities in the production

of suitable reference materials for gluten quantitation. Another analytical topic was the

specificity of different immunochemical kits for gluten quantitation towards gluten

fractions and gluten from different plant species. Two presentations were on the

detection and quantitation of gluten by mass spectrometry and, finally, breeding

approaches on reducing or elimination of coeliac disease activity of wheat and barley

were presented.

Clinical session

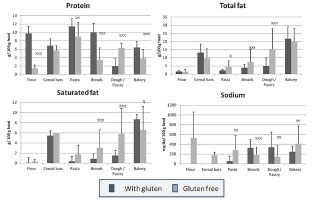

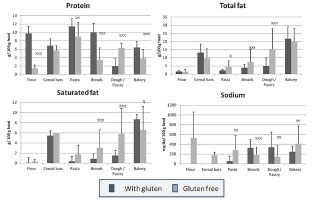

This session also included six presentations. The first talk was on the gluten-free diet

of the Spanish coeliac population and the nutrient intake compared to the glutencontaining

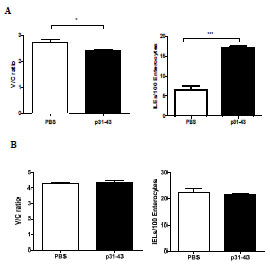

diet. Another presentation was on signalling in the innate immune response

in coeliac disease. A novel approach for endomysium antibody testing by using liver

tissue instead of oesophagus tissue was also presented. A talk on the use of mass

cytometry to image cell populations in different coeliac disease conditions was

followed by a presentation on the activity of avenin from oats in coeliac disease.

Symposium: Innate Immunity and Coeliac Disease

Three recognized experts in innate immunity presented results from their research.

Viral infections as well as gliadin peptides were discussed as potential triggers of the

innate response of the immune system in coeliac disease pathogenesis. Finally,

research on amylase-trypsin-inhibitors (ATI) was presented, which are thought to be

related to the innate response of the immune system. They have been postulated to act

as triggers of non-celiac gluten sensitivity but also as “second” and “third hits” in the

pathogenesis of a number of chronic inflammatory diseases.

4. Analytical research reports

4.1 Comparative analysis of prolamin and glutelin fractions with ELISA test kits

Barbara Lexhaller, Christine Tompos, Peter Koehler, Katharina A. Scherf

Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Lebensmittelchemie, Leibniz Institut, Freising,

Germany

Introduction

Immunochemical methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs)

are specific and sensitive analytical tools for gluten quantitation. They do not require

specialised equipment, are comparatively fast and easy to use also in routine

applications and recommended by legislation [1]. Due to these advantages and lack of

a fully validated alternative method to quantitate gluten proteins, ELISAs are most

commonly used to monitor the safety of gluten-free foods for coeliac disease (CD)

patients. More than 20 ELISA test kits for gluten analysis are currently on the market.

Each of these test kits has its specific features regarding the procedure to extract gluten

proteins from the food matrix, the test format (sandwich or competitive), the reference

material used for calibration (PWG-gliadin [2], gluten or wheat protein), the type of

antibody (monoclonal or polyclonal), and the specificity and sensitivity of the antibody

against different epitopes depending on the antigen that was originally used for

immunisation (Tab. 1). In addition to various polyclonal antibodies (pAbs), current

sandwich ELISA test kits are based on the R5 [3], G12 [4], and 401.21 (Skerritt) [5]

monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Gluten is composed of the alcohol-soluble prolamin

fraction and the alcohol-insoluble glutelin fraction that is only soluble after addition of

disaggregating and reducing agents. Analytical methods should be capable of detecting

the total gluten content, because both prolamins and glutelins harbour CDimmunogenic

epitopes [6]. Most ELISA test kits are assumed to only recognize the

prolamin fraction and the gluten content is calculated by multiplying the prolamin

content by a factor of two. However, detailed comparative studies on antibody

sensitivities and specificities against the prolamin and glutelin fractions from wheat,

rye, and barley are missing. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare these

different gluten fractions within one ELISA test kit as well as to compare the same

gluten fraction between test kits.

Materials and methods

Modified Osborne fractionation and quantitation by RP-HPLC

Flours of wheat (cultivar Akteur), rye (cultivar Visello), and barley (cultivar Marthe)

were sequentially extracted with dilute salt solution (albumin/globulin fraction), 60% (v+v) aqueous ethanol (prolamin fraction) and 50% (v+v) 1-propanol/0.1 mol/L Tris-

HCl, pH 7.5 containing 0.06 mol/L (w+v) dithiothreitol at 60 °C under nitrogen

(glutelin fraction) [7]. After centrifugation, the respective extracts were made up to

volume (2 mL), filtered (0.45 μm) and the gluten protein concentrations were

quantitated by RP-HPLC using PWG-gliadin [2] as calibration reference.

Analysis with ELISA test kits

The fresh prolamin and glutelin extracts were diluted appropriately to fit within the

respective calibration range of the five sandwich ELISA test kits (Tab. 1).

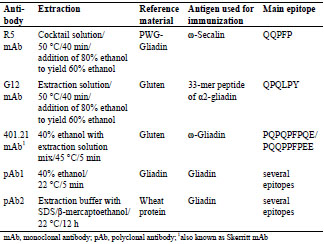

Table 1. Overview of the differences in commercially available sandwich ELISA test

kits used for the comparative analysis of prolamin and glutelin fractions.

Five serial dilutions of each prolamin and glutelin extract were measured in duplicate

with each test kit. The last dilution step was always performed with the sample

dilution buffer included in the test kit and the ELISA procedures were carried out

strictly according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Data analysis

The prolamin and glutelin concentrations quantitated by RP-HPLC were plotted

against the absorbance which was measured by the ELISA test kit. Then the ELISA

protein concentrations were calculated using the respective reference material provided as calibrator in the test kit. This allowed creating plots of the prolamin and

glutelin concentrations quantitated by ELISA against those quantitated by RP-HPLC

(Fig. 1). Ideally, both concentrations would be the same.

Results and discussion

Overall, the comparative analysis of prolamin and glutelin fractions from wheat, rye

and barley with five commercial ELISA test kits for gluten quantitation covered three

different mAbs (R5, G12 and Skerritt) as well as two pAbs. Taking the respective

dilutions into account, the prolamin and glutelin concentrations quantitated by RPHPLC

were always used as independent base values for all calculations and

comparisons of ELISA results.

The specificities and sensitivities of each antibody against the different gluten

fractions were variable within one test kit (Fig. 1). The R5 mAb had the highest

affinity towards rye and barley prolamins as well as rye glutelins. Wheat prolamins

were detected with about equal sensitivity as the kit standard, which was according to

expectations, because PWG-gliadin is used for calibration. The glutelins of wheat and

barley only showed very limited reactivity with the R5 mAb. Wheat, rye and barley

prolamins were detected by the G12 mAb with almost equal sensitivity that was also

comparable to the kit standard. However, the affinity of the G12 mAb towards wheat

and rye glutelins was very low and it was unable to detect barley glutelins, as has been

reported before [8]. In contrast to the R5 and G12 mAbs, the 401.21 (Skerritt) mAb

reacted with wheat, rye and barley glutelins with even higher sensitivity than with the

kit standard. Wheat and rye prolamins and the kit standard were detected with

comparable sensitivity, but the affinity towards barley prolamins was very low. Both

pAbs differed considerably in their abilities to accurately detect wheat, rye and barley

prolamins and glutelins. Wheat and rye prolamins were recognized by the pAb 1, but

all other fractions showed very limited reactivity. The pAb 2 detected all fractions with

high sensitivity except for barley glutelins.

When comparing the analyses of the same gluten fraction with the five different test

kits, the results also showed a high degree of variability. The only exception were

wheat prolamins (gliadins), which were only slightly overestimated by the R5, Skerritt

and pAb 2 assays and slightly underestimated by the G12 and pAb 1 assays. This

result was according to expectations, because most test kits are calibrated against

gliadins. However, wheat glutelins were overestimated about 9-fold by the Skerritt

mAb and underestimated by a factor of about 10 by the R5 and G12 mAbs and the

pAb 1, whereas the pAb 2 yielded results that agreed with the RP-HPLC quantitation.

In the case of rye prolamins, the R5 and pAb 2 assays overdetermined the

concentration, the pAb 1 assay slightly underestimated the concentration and the G12

and Skerritt mAb assays showed a good correlation to the RP-HPLC results. The

immunochemical determination of rye glutelins revealed that this fraction was

overestimated by the R5, Skerritt and pAb 2 assays, but underestimated by up to 10-

fold by the G12 and pAb 1 assays. The analyses of barley gluten fractions showed the highest overall degree of variability. Barley prolamins were overestimated by up to 6-

fold using the R5 and pAb 2 assays, but the pAb 1 and Skerritt assays hardly showed

any detection. The G12 assay resulted in quite accurate values. In contrast, the Skerritt

assay was the only one that was able to detect barley glutelins. All other mAbs and

pAbs showed virtually no affinity towards barley glutelins.

Figure 1. Prolamin and glutelin concentrations [ng/mL] quantitated by RP-HPLC

plotted against the prolamin and glutelin concentrations [ng/mL] quantitated by five

sandwich ELISA test kits using the R5, G12 or 401.21 (Skerritt) monoclonal antibodies

or two different polyclonal antibodies (pAb1 or pAb2)

Conclusions

Different gluten fractions yielded variable results within one ELISA test kit just like

different ELISA test kits yielded variable results within one gluten fraction. The mAbs

and pAbs showed different sensitivities and specificities towards wheat, rye and barley

and towards prolamin and glutelin fractions. Therefore, the gluten content was either

over- (up to 6-fold) or, more seriously for CD patients, underestimated (up to 8-fold).

A careful consideration of this variability of results between different ELISA test kits

is important, especially when analysing samples where the gluten source is unknown.

Aknowledgment

This research was funded by a grant of the German Coeliac Society (Deutsche

Zöliakie-Gesellschaft e. V.) awarded to Katharina Scherf in 2014.

References

1. Scherf KA, Poms RE. Recent developments in analytical methods for tracing

gluten. J Cereal Sci 2016; 67: 112-122.

2. Van Eckert R, Berghofer E, Ciclitira PJ, et al. Towards a new gliadin reference

material – isolation and characterisation. J Cereal Sci 2006; 43: 331-341.

3. Osman AA, Uhlig HH, Valdés I, et al. A monoclonal antibody that recognizes a

potential coeliac-toxic repetitive pentapeptide epitope in gliadins. Eur J

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001; 13: 1189-1193.

4. Moron B, Cebolla A, Manyani H, et al. Sensitive detection of cereal fractions that

are toxic to celiac disease patients by using monoclonal antibodies to a main

immunogenic wheat peptide. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 405-414.

5. Skerritt JH, Hill AS. Monoclonal antibody sandwich enzyme immunoassay for the

determination of gluten in foods. J Agric Food Chem 1990; 38: 1771-1776.

6. Tye-Din JA, Stewart JA, Dromey JA, et al. Comprehensive, quantitative mapping

of T cell epitopes in gluten in celiac disease. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2: 41ra51.

7. Wieser H, Antes S, Seilmeier W. Quantitative determination of gluten protein

types in wheat flour by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography.

Cereal Chem 1998; 75: 644-650.

8. Rallabhandi P, Sharma GM, Pereira M, et al. Immunological characterization of

the gluten fractions and their hydrolysates from wheat, rye and barley. J Agric

Food Chem 2015; 63: 1825-1832.

4.2 Progress towards the practical application of MS for

gluten detection and quantification

Michelle L. Colgrave1, Keren Byrne1, Malcolm Blundell2, Gregory J. Tanner2, Crispin

A. Howitt 2

1 CSIRO Agriculture Flagship, St Lucia, QLD 4067, Australia

2 CSIRO Agriculture Flagship, Black Mountain, ACT 2601, Australia

Introduction

Gluten is the collective name for a class of proteins found in wheat, rye, and barley.

Coeliac disease (CD) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the small

intestine in a subset of genetically susceptible individuals that is triggered by the

ingestion of gluten, resulting in intestinal inflammation and damage. The only current

treatment for CD- and gluten-intolerants (70 million people globally) is lifelong

avoidance of dietary gluten. Gluten-free (GF) foods are now commonplace, however,

it is difficult to accurately determine the gluten content of GF products using current

methodologies as the antibodies are non-specific and show cross-reactivity. In

processed products measurement is further confounded by protein modifications

and/or hydrolysis. The development of mass spectrometry- (MS) based methodology

for absolute quantification of gluten is required for the accurate assessment of gluten,

including hydrolysed forms, in food and beverages to support the industry, legislation

and to protect consumers suffering from CD.

In this study, the hydrolysis of gluten was examined by proteomic profiling of beers

subjected to size-fractionation. Selected proteolytic and hydrolysed peptide fragments

were quantified by targeted mass spectrometry and the results were compared with

ELISA data. Strikingly, those beers containing high levels of hydrolysed B-hordeins

yielded potential false negatives by ELISA. The effect of the hydrolysed gluten

fragments on the suppression of ELISA response was further investigated revealing

interference that precludes the accurate quantification of beers using sandwich ELISA

technology. Secondly, proteomic profiling of gluten-enriched fractions of 16 cereal

grains including wheat, rye, barley, and oats focussing only on the grain (the edible

seeds) provided the foundation for the selection of peptide markers unique to wheat. A

rapid, robust, selective and sensitive method for detection of wheat contamination in a

range of cereals using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) MS was developed and

applied to detect contamination in commercially available flour as well as in an

intentionally contaminated soy flour.

Materials and methods

Suppression of ELISA by hydrolysed gluten

A selection of beers were collected (60 commercial beers and a lab-brewed beer made

using barley cv. Sloop as listed in [1]) based on the stated ingredients or gluten

content. Each beer was either: left whole or applied to a 30 k or 10 k molecular weight

cut-off filter as described in [2]. The beers (whole and sub-30 k) were reduced by

addition of 10 μL of 50 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) under N2 for 30 min at 60C. To

these solutions, 10 μL of 100 mmol/L iodoacetamide (IAM) was added and the

samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. To each solution, with the

exception of the 10 k fractions, 5 μL of 2 mg/mL trypsin was added and the samples

incubated at 37 C overnight. The digested peptide solution was acidified by addition

of 50 μL of 1% formic acid and stored at 4 C until analysis. All beer samples

generated were analysed by liquid chromatography (LC-) MS/MS and proteins

identified by automated database searching as described in [2]. Selected proteins (and

their peptide fragments) were further analysed by targeted proteomics employing

MRM MS [2].

Three beers were selected from the collection. Beers 6 and 31 gave a high and medium

response by ELISA, respectively. Beer 13 gave near-zero ELISA response, but

contained average levels of hordein by MS and high levels of hydrolysed gluten by

MS. Beer 13, either undiluted or diluted 2-, 5- or 10-fold was added to sandwich

ELISA wells containing beers 6 or 31 which had been diluted 1/50,000 or 1/5,000

respectively (so as to be in the middle of the Sloop hordein standard curve as described

in [3]). In a second experiment, aliquots of beer 13, either unfiltered or filtered through

100, 30, 10 or 3 k molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filters were added to sandwich

ELISA wells followed by aliquots of beers 6 or 31. All ELISA assays were processed

according to manufacturer’s instructions (ELISA Systems) and as described in [2].

Detection of wheat (gluten) contamination

Grains of wheat cv. Chara and 15 commercially relevant cereal grains were sourced as

described in [4]. A gluten-enriched fraction was prepared by dissolving wholemeal

flour (20 mg) in 200 μL 55% (v+v) propan-2-ol (IPA), 2% (w/v) dithiothreitol (DTT)

with incubation at 60 C for 30 min. The total protein extraction was performed by

dissolving wholemeal flour (20 mg) in 200 μL of 8 M urea, 2% (w/v) DTT with

incubation at RT for 30 min. The solutions were centrifuged for 15 min at 20,800 x g

and the supernatant was kept. The proteins were reduced, alkylated and digested using

trypsin [4] prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

Results and discussion

Suppression of ELISA by hydrolysed gluten

We have previously demonstrated that barley-based beers that contain seemingly

average levels of hordein by MS have very low or zero readings by ELISA [5]. We have also demonstrated the existence of hordein peptide fragments in beers that have

been filtered through 10 k molecular weight cut-off filters with no enzymatic digestion

[1]. In this study, we sought to examine the relationship between the levels of

hydrolysed hordein in beer with the effect on the ELISA response.

LC-MS/MS analysis of barley-derived beers revealed that certain classes of hordein

were prone to hydrolysis (as judged by the percentage of each hordein present in the

30 k fraction relative to whole beer). Specifically, 57 + 12% and 37 + 7% hydrolysed

hordein were detected for B1- and B3-hordein, 31 + 13% for D-hordein compared to

18 + 10% for γ3-hordein. The resulting peptide fragments shared significant homology

with the immunotoxic epitopes determined for CD (Tab. 1). Strikingly, those beers

that contained high levels of B-hordein fragments gave near zero values by ELISA.

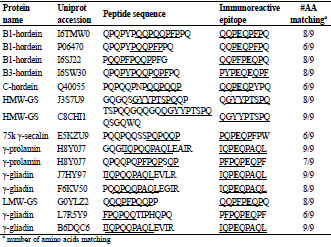

Table 1. Potential immunoreactive peptide sequences. Peptide sequences identified

(>95% confidence) in the sub-10 k fraction of 60 commercial beers. The sequences

are aligned with the closest matching immunoreactive epitope(s). Glutamic acid

residues shown in bold typefont (E) are produced by deamidation of glutamine (Q) by

the enzyme tissue transglutaminase, but are present as Q in the native protein.

Gluten fragments detected in the sub-10 k fraction contained epitopes that would likely

be recognized by the antibodies used in currently accepted ELISA assays. The Skerritt

antibody recognizes PQPQPFPQE & PQQPPFPEE, while the Mendez R5 antibody

recognizes QQPFP, QQQFP, LQPFP & QLPFP. Typical examples of gluten hydrolysis fragments detected include: B1-hordein (Uniprot: P06470 and I6SJ22)

peptide fragments QPQPYPQQPFPPQ and PQQPFPQQPPFG; B3-hordein (Uniprot:

I6SW30) peptide fragment QPQPYPQQPQPFPQ. QPQPYPQQPFPPQ shares 6/9 in

the DQ8 T cell epitope (EQPQQPFPQ) and PQQPFPQQPPFG shares 8/9 residues in

the DQ2 T cell epitope (QQPFPEQPQ) rendering them likely to possess

immunoreactivity.

The hydrolysed fragments that persist in beer show a dose-dependent suppression of

ELISA measurement of gluten despite using a hordein standard for calibration of the

assay. One drawback of sandwich ELISAs is they cannot adequately quantify gluten

that has been highly hydrolysed [6]. Sandwich ELISAs require two epitopes or

antibody binding sites. When a protein is hydrolysed, the various fragments may not

contain two epitopes. Many of the hydrolysed gluten fragments present in beer 13 have

one potential antigenic site. It was hypothesised that their binding to the capture

antibody precludes the binding of intact gluten proteins resulting in suppression of the

ELISA response. Beer 13 showed a concentration-dependent suppression of the

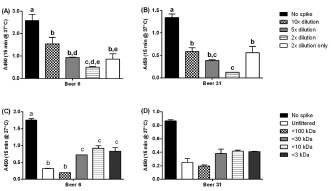

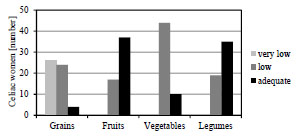

ELISA response (Fig. 1A, B) in both a high-gluten containing wheat beer (beer 6) and

a medium gluten-containing beer (beer 31). The suppression was demonstrated to be

due primarily to the <3 k fraction, i.e. hydrolysed peptide fragments (Fig. 1C, D).

Suppression was also caused by the high MW fraction (30 - 100 k) possibly the result

of aggregation (Fig. 1C, D).

Figure 1. Suppression of ELISA response by hydrolysed gluten present in whole beer.

Beer 13 (that contained high levels of hydrolysed gluten) was spiked into samples of

beers with differing levels of total gluten: (A) beer 6 (high); or (B) beer 31 (medium).

The columns represent (from left to right) no spike, spike with diluted beers (at either

10-, 5- or 2-fold dilutions) or the 2-fold diluted spike only. The mean A450 ± SD are

shown. Beer 13 was subsequently subjected to size-fractionation prior to addition in to

the same two beers: (C) beer 6; and (D) beer 31. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was

carried out (2D: A and B; 1D, C and D). Within a group, columns with different letters

were significantly different by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p ≤ 0.01)

Detection of wheat (gluten) contamination

In this study, 16 cereal grains that may be subject to contamination have been

comprehensively characterised using discovery proteomics to identify wheat-specific

peptide markers. As the focus of our work is the detection of gluten proteins, an

IPA/DTT extract that has been shown to preferentially solubilise the gluten fraction

[3,7] was used. In order to accurately identify the specific gluten isoforms present in

the extract, a combination of three proteolytic enzymes: trypsin, chymotrypsin and

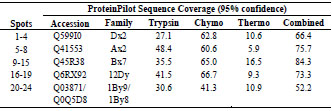

thermolysin; was used to improve the protein sequence coverage (Tab. 2).

Table 2. Identification of HMW-glutenin isoforms was achieved using a combination

of three proteolytic enzymes by obtaining maximum sequence coverage.

The tryptic peptide products identified in the global LC-MS/MS analyses were

assessed to identify prototypic peptides that were unique to wheat and that were high

responding in the MS analysis, that is, peptides that yielded good peak area/intensity.

The peak area/intensity is dependent on the ionisation efficiency of the peptide, but

also the abundance of the protein and, therefore, the peptide and the efficiency of

proteolytic digestion under the experimental conditions. The top 20 highest responding

peptides were selected and subjected to BLASTp analysis (NCBI BLASTp server)

against all other cereals to ensure specificity to wheat based on protein sequences that

exist in the public databases. As not all of the grains examined have been sequenced at

the genome level, it was expected that the public databases would be incomplete. To

ensure the selected peptide markers were wheat-specific, the 16 grain extracts were

screened using the LC-MRM-MS method developed herein. Peptide MRM transitions

that showed interference, broad peaks and/or low intensity peaks were excluded from

further analysis. The 10 best wheat peptides were selected for subsequent MRM

analyses.

Figure 2. From the top 10 wheat-specific peptide markers (A), the best 4 were selected

(B) and allowed the detection of wheat contamination in rye (C) and millet (D) flour.

Detection of contamination in commercial products: (E) Flour from rye, millet,

sorghum, buckwheat, and oats were confirmed with low level wheat contamination

Fig. 2 shows the LC-MRM-MS analysis targeting the wheat-specific peptide markers.

The total ion chromatogram (TIC, Fig. 2A) shows ten peptide markers (labelled P1-

P10) from which peptides P3, P4, P7 and P9 were selected and are shown in the

extracted ion chromatogram (XIC, Fig. 2B). Fig. 2E shows the results of the LCMRM-

MS analysis of 16 grains using four wheat-specific peptide markers. As

expected, the markers were present in high abundance in wheat, green wheat (Freekeh)

and spelt. However, all four peptide markers were also detected in rye (average MRM

peak area 4.2% relative to wheat), in millet (0.3%), and buckwheat (0.02%), whilst three of the four peptide markers were detected in sorghum (0.03%) and oats (0.05%).

The XIC for the analysis of pre-milled rye (Fig. 2C) and millet (Fig. 2D) flour

revealed peaks matching to all four peptide markers (P3 at 3.6 min; P4 at 4.0 min; P7

at 5.5 min; and P9 at 7.3 min) indicating that the commercial flour samples of both rye

and millet were contaminated by wheat (4.2% in rye and 0.3% in millet).

Uncontaminated whole grain of rye and millet were obtained, visually inspected,

milled to fine flour after careful cleaning of the mill, analysed and shown to be devoid

of wheat confirming the detection of the peptide markers was due to wheat

contamination and not the presence of endogenous proteins. Trace levels of the wheat

peptide markers were also observed in commercial flours from oats, sorghum, and

buckwheat, but the levels detected were <0.05% relative to wheat.

Figure 3. Peptide markers are useful for diverse wheat varieties. The wheat peptide

markers were assessed across 14 commercial wheat lines (A) and nine MAGIC parent

lines (B)

The wheat peptide markers were selected from analysis of a single wheat cultivar

Chara. In order to assess the utility of the wheat peptide markers in broader

applications, we investigated their presence and level in 14 commercially available

wheat cultivars and in nine parent lines of the 4 and 8 way MAGIC populations

developed by CSIRO [8], that are thought to represent 80% of the genetic diversity

within the bread wheat genome (Fig. 3). Variation in the peptide levels of 22-26% for

the 14 commercial lines and 11-16% for the nine MAGIC parent lines for P4, P7 and

P9 was observed. Only one peptide (P3) was absent in the wheat cultivar Xioayn, a

Chinese winter cultivar used for noodles, and showed higher variation between

cultivars (43-57%). Overall, these data demonstrate that the selected peptide markers

are suitable for detection of wheat across a wide variety of wheat representative of

those used commercially.

Conclusions

Analysis of barley-derived beers revealed that high levels of gluten (B-hordein)

hydrolysis correlated with low values by ELISA. The hydrolysed fragments that

persist in beer caused a dose-dependent suppression of ELISA gluten measurement.

Global proteomic analysis of 16 economically important cereals utilising SDS-PAGE,

Western blotting and LC-MS/MS was used to characterise the “gluteome” and select peptide markers specific to gluten and/or wheat for targeted quantitative MS assays.

Wheat-specific peptide markers were detected in 14 wheat varieties that together

constitute 80% of modern wheat genetic diversity and facilitated the detection of

wheat contamination in commercial flours.

References

1. Colgrave, ML, Goswami H, Howitt CA, et al. What’s in a beer? Proteomic

characterisation of hordein (gluten) in beer. J Proteome Res 2012; 11: 386-396.

2. Colgrave, ML, Goswami H, Blundell M, et al. Using mass spectrometry to detect

hydrolysed gluten in beer that is responsible for false negatives by ELISA. J

Chrom A 2014; 1370: 105-114.

3. Tanner GJ, Blundell MJ, Colgrave ML, et al. Quantification of hordeins by

ELISA: The correct standard makes a magnitude of difference. Plos ONE 2013; 8:

e56456.

4. Colgrave, ML, Goswami H, Byrne K, et al. Proteomic profiling of 16 cereal

grains and the application of targeted proteomics to detect wheat contamination. J

Proteome Res 2015; 14: 2659-2668.

5. Tanner GJ, Colgrave ML, Blundell MJ, et al. Measuring hordein (gluten) in beer– A comparison of ELISA and mass spectrometry. Plos ONE 2013; 8: e56452.

6. Thompson T, Mendez E. Commercial assays to assess gluten content of glutenfree

foods: Why they are not created equal. J Am Diet Assoc 2008; 108: 1682-

1687.

7. Ribeiro M, Nunes-Miranda JD, Branlard G, et al. One hundred years of grain

omics: identifying the glutens that feed the world. J Proteome Res 2013; 12: 4702-

4716.

8. Huang BE, George AW, Forrest KL, et al. A multiparent advanced generation

inter-cross population for genetic analysis in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J 2012; 10:

826-839.

4.3 Studies on the analysis of gluten-containing cereals

Kathrin Schalk, Katharina Scherf, Peter Koehler

Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Lebensmittelchemie, Leibniz Institut, Freising,

Germany

Introduction

Coeliac disease (CD) is an inflammatory disorder of the upper small intestine caused

by the ingestion of gluten proteins from wheat (gliadins, glutenins), rye (secalins),

barley (hordeins), and possibly oats (avenins). The only effective therapy for CD

patients is a strict gluten-free diet by consuming gluten-free foods, which contain less

than 20 mg gluten/kg [1]. To ensure the safety of gluten-free products for CD patients,

it is essential that appropriate analytical methods with high specificity and sensitivity

are available. The most commonly used method for gluten analysis is an enzymelinked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Currently, the ELISA based on the R5

monoclonal antibody is endorsed for gluten analysis in maize-matrices [2] and is

defined as type I method [3]. In general, with ELISA it is only possible to determine

the prolamin content in foods, and not the whole gluten content. The gluten content is

then calculated by multiplying the prolamin content by a factor of 2. This calculation

is based on the assumption that the ratio of prolamins to glutelins is 1. The problem is

that different types of grains contain different proportions of prolamins and glutelins.

As a result, the gluten content may be either over- or underestimated. In particular the

latter is problematic for CD patients [4].

Therefore, a new independent non-immunochemical method for the quantitation of

prolamins and glutelins (= total gluten) is urgently needed to verify the results

determined by ELISA. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS/

MS) appears to be a suitable method for the quantitation of gluten.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify marker peptides from wheat, barley,

rye, and oats to develop a stable isotope dilution assay for the quantitation of intact and

partially hydrolysed gluten.

Materials and Methods

Defatted flours from wheat, barley and oats (a mixture of four cultivars of each grain,

harvest 2013) were extracted by a modified Osborne procedure [5]. First,

albumins/globulins were extracted with 0.067 mol/L K2HPO4/KH2PO4-buffer with 0.4

mol/L NaCl (pH = 7.6) at 20 °C. Second, the residue was extracted with 60% (v+v)

ethanol at 20 °C to obtain the prolamin fraction. Finally, the glutelin fraction was

extracted with 50% (v+v) 1-propanol/urea/Tris-HCl/dithiothreitol (pH = 7.5) at 60 °C.

Albumins/globulins were discarded because they were not relevant for gluten analysis. Different protein types were isolated using preparative reversed-phase highperformance

liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). Gliadins (wheat) were separated into ω5-, ω1,2-, α-, and γ-gliadins, and glutenins (wheat) were separated into lowmolecular-

weight- (LMW-GS) and high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (HMWGS).

Barley prolamins were divided into γ- and C-hordeins, and barley glutelins into

B- and D-hordeins. Furthermore, all isolated protein types and fractions were

characterized by sodium dodecylsulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDSPAGE)

to verify the molecular weights and the purity of the preparations.

In order to be able to develop a LC-MS/MS method for gluten proteins, partially

hydrolysed reference proteins were necessary. For this purpose, the isolated reference

proteins (protein types, protein fractions) as well as the flours were incubated with

chymotrypsin for 24 h at 37 °C and pH 7.8 (ratio enzyme:protein; 1:200). After

incubation, the peptide mixtures were purified by solid phase extraction on DSC-18

cartridges. Then, the hydrolysates were analysed by LC-MS/MS.

Results and Discussion

Prolamin and glutelin fractions from wheat (gliadins/glutenins) and barley (hordeins)

were separated into protein types by preparative RP-HPLC. Avenins were not further

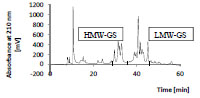

separated. As an example, Fig. 1 shows the chromatogram of the glutenins, which

were separated into HMW- and LMW-GS. All isolated protein types were characterrized

by RP-HPLC and SDS-PAGE to verify the range of the molecular weights.

Figure 1. Preparative RP-HPLC of isolated wheat glutelins (glutenins; 25 mg/mL,

injection volume: 300 μL). HMW-GS, high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits; LMWGS,

low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits

All isolated protein types from wheat, barley, and oats were hydrolysed and analysed

by LC-MS/MS to identify gluten marker peptides which will be used for gluten

quantitation. These marker peptides must fulfil specific requirements to be suitable for

gluten quantitation. Firstly, the amino acid sequences must be characteristic for each

protein type. Ideally, the peptide sequences should not occur in other protein types of

gluten or other proteins. Secondly, the marker peptides should have a peptide length of

8 to 20 amino acids, because too small peptides are not specific enough and peptides

longer than 20 amino acids are unsuitable for quantitation due to high complexity and the large number of fragments. Thirdly, the marker peptides should not contain

cysteine residues because of their tendency to oxidation.

To define gluten marker peptides, all isolated protein types from wheat and barley

were hydrolysed and analysed by LC-MS/MS in the first step. By using the NCBIDatabase

(National Center for Biotechnology Information) and the MASCOT-software

(Matrix Science, London, UK), gluten peptides were identified. In the second step, the

criteria for gluten marker peptides were applied to get candidate peptides. To verify

this selection, all protein fractions from wheat, barley, and oats as well as the flours

were hydrolysed and analysed by LC-MS/MS. Finally, peptides which were identified

in all hydrolysates (protein type, protein fraction and flour) and which fulfilled the

requirements were suitable for gluten quantitation. For each protein type, two or three

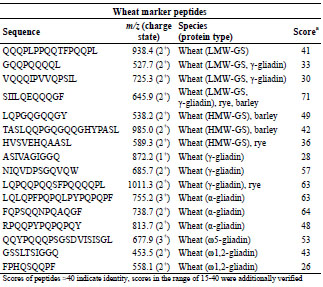

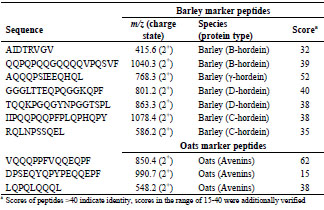

gluten marker peptides were defined (Tab. 1 and Tab. 2). For ω5-gliadin, only one

marker peptide was defined because of the low amount in flour.

Table 1. Selection of marker peptides for wheat gluten, their mass-to-charge-ratios,

and the peptide scores, which were detected in flour.

In general, it was also an important criterion to select marker peptides with a high

score to increase the chance to detect them in different food matrices. Although the oat

peptide DPSEQYQPYPEQQEPF was detected with a low protein score of 15, it was

defined as marker peptide because it contains a deamidated T cell epitope

(PYPEQEQPF) (Tab. 2) [6].

Table 2. Selection of marker peptides for gluten from barley and oats, their mass-tocharge-ratios, and the peptide scores, which were detected in flour.

Conclusions

The LC-MS/MS analysis of hydrolysed proteins from wheat, barley and oats yielded a

number of peptides which can be used as gluten marker peptides. Peptides, which were

identified in hydrolysed protein types, protein fractions as well as the flour, were

selected as marker peptides. For each protein type, two to three marker peptides were

defined, which provide the basis to develop a non-immunochemical independent

method for gluten quantitation.

References

1. Wieser H, Koehler P. The biochemical basis of celiac disease. Cereal Chem 2008;

85(1): 1-13.

2. Koehler P, Schwalb T, Immer U, et al. AACCI approved methods technical

committee report: collaborative study on the immunochemical determination of

intact gluten using an R5 sandwich ELISA. Cereal Foods World 2013; 58: 36-40.

3. Codex Standard 324-1999, 2014. Recommended methods of analysis and

sampling. Codex Alimentarius Commission. Amendment 4.

4. Wieser H, Koehler P. Is the calculation of the gluten content by multiplying the

prolamin content by a factor of 2 valid? Eur Food Res Technol 2009; 229: 9-13.

5. Wieser H, Antes S, Seilmeier W. Quantitative determination of gluten protein

types by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. Cereal Chem

1998; 75 (5): 644-650.

6. Londono DM, van’t Westende WPC, Goryunova S, et al. Avenin diversity

analysis of the genus Avena (oat). Relevance for people with celiac disease. J

Cereal Sci 2013; 58: 170-177.

4.4 Strategies to reduce or prevent wheat coeliacimmunogenicity

and wheat sensitivity through food

Luud J.W.J. Gilissen1, Ingrid M. van der Meer1, Marinus J.M. (René) Smulders2

1 Wageningen UR, Bioscience, Wageningen, The Netherlands

2 Wageningen UR, Plant Breeding, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Abstract

Cereals are among the oldest foods of humans. Wheat is one of these. In present times,

several syndromes are, whether true or false, increasingly attributed to the consumption

of wheat, with increasing costs for medical care and decreasing turnover for the

food industry, especially the bakery sector. Many western societies show remarkable

annual increases in their health care costs, often surmounting their economic growth

rates. Governmental health policies should urgently revert towards the stimulation of

disease prevention practices instead of maintaining the stimulation of expensive

medical care.

Here we review and discuss possible strategies to prevent or reduce the incidence of

wheat-related conditions through application of breeding and food-related

technologies. Breeding includes selection and crossing for low-immunogenic wheat

varieties using varieties, accessions, and wild relatives, silencing the expression of

gluten genes, and advanced genome editing techniques to eliminate gluten genes, such

as CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Food-related approaches include the reduced application

of vital gluten, exclusion of gliadin from isolated gluten by separation, increased use

of sourdough fermentation and malting, utilisation of patient-specific gluten epitopesensitivity

profiles, introduction of the gluten contamination elimination diet (GCED)

especially in individuals that are non-responsive to the gluten-free diet, to acquire

more fundamental knowledge on immune modulating factors, and the design of an

intervention study to learn about the medical and mental motives of people to switch

towards a ‘gluten-free’ diet. Finally, we discuss the development, testing and

promoting of efficient disease prevention measures within the societal context.

Introduction

Agriculture started some 10,000 years ago. It is a myth, however, that the consumption

of cereal grains by humans begun only at that time. The divergence of early

humanoids from man-apes occurred about 6 My ago with leaving the African forest

and moving into the savannah areas. Concomitantly, the humanoids increased their

feeding on small and hard grass (cereal) seeds. This has been concluded from the

shape of the molars and the increased thickness and the molecular composition of the

enamel [1-3]. From 1.5 My ago onwards, Homo species increased the fraction of C4-

based plant resources (i.e. cereals) in their diet as was also concluded from enamel analysis [4]. As early as 120,000 years ago, during an interglacial period, the Levant,

where barley and wheat are endemic species, was a fruitful settling and meeting place

where West-European Neanderthals exchanged genes with early modern humans [5].

Neanderthals from the Iraq region are known to have consumed cooked Triticeae

grains, especially barley, about 50,000 years ago [6]. Excavations from 32,600 years

ago in Italy revealed the occurrence of thermal pre-treatment and grinding of cereal

seeds (oats) by humans [7] indicating that cereal food technology must have been

developed much earlier. From more recent times, some 15,000 years ago, remainders

from barley groat meals and porridge have been found, as well as remains from

unleavened bread from barley flour [8]. Further, data from 11,000 years ago show

ground collection of wild barley and wild emmer wheat seeds as an intermediate step

between seed collection by hunter-gatherers and cereal harvesting by early farmers [9].

Agriculture and cereal (barley and wheat) consumption, therefore, did not appear

suddenly 10,000 years ago, but had a long and gradual origin.

Remarkable in this apparently long tradition of grain consumption by humans is the

development of bread wheat and spelt wheat (both with the AABBDD genome). These

wheats are considered as the natural hybrids between (early cultivated) emmer wheat

(with AABB genome) and wild Triticum tauschii (with the DD genome). The

hybridization is suggested to have occurred some 8,000-9,000 years ago, maybe as a

side-result of early agricultural activity [10]. More recently, 2,000 years ago, coeliac

disease (CD) was identified (but not yet directly related to the consumption of wheat,

barley and rye) and received its name from Arathaeus of Cappadocia [11].

Undoubtedly, this disease must have existed much longer and most probably at

significant frequency.

In the 20th century cereal breeding and cereal food processing have become highly

advanced. Wheat and barley can be grown now also at high latitudes and large

acreages. Millers are able to refine cereal meal and separate many fractions that can be

used in innumerable applications. Simultaneously, the prevalence of and mortality due

to undiagnosed CD increased four times [12]. During the last years, non-celiac

wheat/gluten sensitivity (NCWGS) seems a new condition, although some case reports

were already known from the seventies of last century [13,14]. A recently estimated

prevalence in the general population of NCWGS, obtained from indirect evidence, is

slightly more than 1% (which is similar to the prevalence of CD in the general

population [15]). NCWGS is mostly reported to occur in females in the age group of

30-50, although also paediatric cases are known. In spite of the generally low

estimated prevalence of both CD and NCGWS, more than 10% of the adults in the

USA and the UK changed their diet towards gluten-free, mainly on the basis of selfdiagnosis

[15]. The situation may be even more extreme in the USA, where 30% of

restaurant visitors demand gluten-free food [16]. Nevertheless, in NCWGS a direct

relationship with gluten itself or with other wheat-related compounds like amylase

trypsin inhibitors (ATI), lipid transfer proteins (LTP), fermentable sugar compounds

(FODMAPS), or other compounds or factors as causing agents remains unclear [15].

This situation is different for CD. While the relationship with gluten consumption has been established clearly and is well-understood, 80-90% of the CD patients has not yet

been diagnosed or has been diagnosed wrongly. This large part of the CD population

maintains the daily consumption of gluten-containing foods, unaware of the risk of

worsening their health status. These figures together show an underestimated

population of people with CD, and a self-overestimated population of NCWGS people,

both following a (strict) gluten-free diet.

In this short review we propose a broad array of strategies to meet the desire of CD

and NCWGS populations and individuals for safe(r) cereal food (see also [17-19]).

These strategies fall into two categories: ‘plant-related strategies’ that use various

advanced breeding technologies for the reduction of the occurrence of CD epitopes in

especially gliadins, and ‘food-related strategies’ that focus on targeted processing to

enable gluten avoidance.

Plant-related strategies

Selection

Selection of low CD-toxic wheat varieties and accessions has been performed using

epitope-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): out of hundreds of such lines only a

few gave a relatively low mAb response [20,21]. The utility of screening with epitopespecific

mAbs is limited as they do not recognize the complete epitope (mAbs

recognize a maximum linear sequence of six amino acid residues, whereas the T cell

epitope is nine amino acids long) and the signal may be ambiguous and not

quantitative (i.e., also responding to non-intact epitope sequences). A direct approach

combining deep sequencing of the N-terminal region of gliadin transcripts as a prescreening

of developing seeds of a single variety, followed by quantitative proteomics

of ripe seeds [22] enabling simultaneous quantification of several CD epitopes is much

more straightforward and conclusive.

Traditional breeding

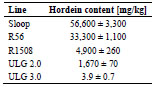

In barley, a reduction of the gluten (hordein) content to below 5 mg/kg (the threshold

for gluten content in ‘gluten-free’ products in the Codex Alimentarius is 20 mg/kg)

was achieved using traditional breeding strategies by combining three recessive

alleles, which act independently of each other to lower the hordein content in the

parental varieties. Further breeding was applied to increase the grain size to near wildtype

levels. The plants were agronomically acceptable and the produced grains showed

good malting characteristics and brewed successfully. The advantage in traditional

breeding of barley over bread wheat is its diploid genome level and the occurrence of

only four hordein protein families [23].

Synthetic hexaploids

The D-genome of bread wheat contributes most to CD-immunogenicity with the

highest number and diversity of epitopes [24], but shows the lowest degree of variation

compared with the A- and the B-genome. Newly created synthetic hexaploids carrying a diversity of D-genomes are now in a screening program which aims to identify

hexaploid wheat lines with reduced CD-immunogenicity [18].

Deletion of loci

A ‘deletion line’ lacking a large part of the short arm of chromosome 6D, which

eliminated the 6D alpha-gliadin locus, showed strongly decreased mAb responses

against the Glia-alpha1 and Glia-alpha3 epitopes. Changes in dough mixing properties

of this line could be compensated by the addition of oat prolamins (avenins), which are

not CD-immunogenic. Such deletion lines are especially useful as model systems but

lack economic value as they grow poorly. This is probably an effect of the loss of

hundreds of other genes on this chromosome arm [25].

RNAi

Two different approaches have been applied to reduce the amount of gliadins in wheat

through silencing of gliadin gene expression using RNA interference (RNAi). In the

first approach, the gliadin genes themselves were targeted directly and successfully

[26-31]. Flour made from grains in which gliadins were silenced showed no T cell

elicitation, but retained baking quality [30]. The other approach used RNAi to suppress

homologs of the DEMETER (DME) gene. This gene encodes a 5-methylcytosine

DNA glycosidase which demethylates the promoter region of gliadin and LMW

glutenin genes in wheat endosperm, a step that is necessary to switch on the expression

of these genes during endosperm development. Suppression of expression of DME

resulted in >75% reduction in the amount of immunogenic prolamins [32].

Mutation breeding and genome editing

Mutation breeding is a relatively old technology using chemical (especially ethyl

methane sulfonate, EMS) or ionizing irradiation (e.g. gamma-radiation, fast neutrons)

to introduce random mutations in the DNA. Mutation selection on populations of

mutant progenies can be carried out through Targeting Induced Local Lesions in

Genomes (TILLING), a technology based on molecular DNA sequence analysis

followed by bioinformatics analysis. It is expected that no single line from such an

experiment would exist in which all gliadins have been mutated simultaneously, but

this strategy may be used in combination with other strategies mentioned above.

Precise genome editing recently sees a stormily increasing interest as the

CRISPR/Cas9 technology enables inducing mutations and deletions at specific,

targeted locations within the genomes of animals as well as plants. Several groups

currently apply CRISPR/Cas9 in wheat, but no results have been published yet.

Food-related strategies

Reduction of vital gluten

Vital wheat gluten is a major side-product in the production of wheat starch which is

the raw material for further production of native and modified starch, glucose syrup,

liquid and crystalline polyols, maltodextrins, all with high-impact applications in the

food industry. Wheat starch is also used for the production of alcohol, including

bioethanol. Since wheat starch is economically the most important product from wheat

(much more important than flour for bakery purposes), the production of its sideproduct,

vital gluten, is enormous. Vital gluten is increasingly applied as protein

additive in food products for technological improvement. The large-scale addition of

vital gluten to a wide range of processed food products has contributed to the increase

in total gluten consumption: between 1977 and 2007, gluten intake in the western

world has tripled [33], and most of this increase took place after 2000. The increase

relates only partly to bread and bakery products, where vital gluten is applied to

maintain high loaf volumes, but is mainly the result of its use in the form of ‘hidden’ ingredient, often not labelled, in a large number of food products. Currently, a

movement is going on in the modern bakery in The Netherlands towards ‘back to

basics’. This includes ‘clean label’ strategies and avoidance or strong reduction of the

application of bread quality-improving ingredients such as enzymes and vital gluten in

artisanal and industrial whole grain breads. There are, however, no indications of

reduced application of vital gluten in other sectors of food production. On the contrary,

more and more vital gluten application in foods is occurring. In addition, industrial

conversion of wheat starch into other food-grade carbohydrates will not eliminate all

stable and potentially immunogenic gluten. Therefore, foods containing these modified

carbohydrates may still contain low levels of gluten. Together these processes have led

to a steady increase of gluten accumulation in the general daily diet.

Elimination of gliadins from gluten

HMW-glutenins give dough its elasticity, while the gliadins can be replaced by other

proteins, e.g. by the coeliac-safe avenins, for maintaining good baking quality [25].

The HMW-glutenins also have a relatively low coeliac-immunogenicity. This means

that separation of glutenins from total gluten is a realistic option that may contribute to

new applications in foods aiming at a strongly reduced immunogenic gluten load.

Nearly complete separation can be achieved at lab scale [34]. Industrial upscaling to

economically and technologically viable levels seems to be more recalcitrant [35], and

would need further research.

Sourdough fermentation

In Germany, the prevalence of CD (measured using a single antibody test) was found

to be remarkably low: 0.4% and 0.2% in women and men, respectively [36], which

confirmed earlier data showing 0.1-0.4% prevalence on the basis of anti-tTG and EMA

positivity [37]. Recent estimations of the CD prevalence in Germany go up to 0.8%, especially in children up to 17 years old [38]. The authors suggest that this may reflect

underdiagnosis in earlier studies, but another explanation is also possible.

Germany has a longstanding tradition of sourdough bread consumption. Sourdough

fermentation has been suggested to enable the manufacture of ‘gluten-free’ or ‘low-ingluten’ wheat-based products through proteolytic gluten degradation [39]. More

recently, a two-step hydrolysis including fungal peptidases and Lactobacillus endopeptidase

activity, respectively, resulted in a wheat flour-derived product with a gluten

content below 10 mg/kg. This product appeared not harmful to individuals with CD

[40]. These observations are promising, but need further research on the potential of

sourdough products in a safe ‘gluten-free’ diet for individual cases. For this, first a

strict definition of the type of sourdough is required and the process of gluten

degradation needs to be analysed in detail. Further, the question is whether large-scale

consumption by the general population of well-defined sourdough products can indeed

contribute to the reduction of the incidence and symptom severity of CD and NCWGS.

The answer requires large-scale epidemiologic research. If sourdough indeed reduces

the exposure to intact gluten epitopes, then the recent increase in prevalence of CD in

young people may in fact reflect a change in the diet of German children and

adolescents towards fast food consumption (white and yeast-based bread).

Malting

This process is not only relevant for brewing, but has also been applied since ages in

the bakery sector. Endogenous proteolytic enzymes become active during malting, i.e.

the first steps in seed germination, to produce amino acids from the storage proteins in

the endosperm as building blocks for new structural and house-keeping proteins for the

young growing seedling. During this germination process, which lasts several days

until the seed has been transformed into a seedling, gliadins may become degraded

first. This means that (specific) gliadinases will show early activity. Application of

enzyme supernatants from a small stock of germinated seeds (especially barley seeds)

have recently been suggested to be applicable in large-scale production of flour

reduced in prolamin content [41,42]. In addition, it has been shown that germinated

and fermented rye and wheat sourdough effectively degraded 99.5% and 95% of the

prolamins, respectively [43,44].

Patient-specific epitope-sensitivity profile

Genomic data of plant species and cultivars are rapidly increasing in number and

detail; this also includes the wheat genome (with the sequences of dozens of gluten

(gliadin) genes and epitopes and their expression profiles). Similarly, genomic data of

humans, also at the individual level, are laying the basis for personalized food and for

personal health and medical strategies. Individuals with CD appear to have different

and epitope-specific sensitivities to gluten [45,46]. Combining both these sets of

gliadin (gluten) and human genomics data may reveal possibilities to further

investigate wheat varieties with epitope profiles that may fit to the specific sensitivity

profile of an individual patient or specific groups of patients.

Gluten contamination elimination diet (GCED)

Some coeliac patients have persistent symptoms and villous atrophy despite strict

adherence to a gluten-free diet. They are referred to as having ‘non-responsive CD’, a

subset of which may have true ‘refractory CD’. Some non-responding CD patients

simply react to minor amounts of gluten, which may be present as contamination in

regular, processed gluten-free foods. As mentioned above (in the paragraph on ‘Reduction of vital gluten’) foods labelled as gluten-free may contain minor amounts

of gluten or stable gluten fragments due to their introduction into these food products

through complex food processing. This may even happen in increasing numbers. Most

(over 80%) of the non-responsive patients, however, improved on a so-called ‘gluten

contamination elimination diet’ (GCED) that included only fresh and unprocessed

foods. These patients appeared not to suffer from ‘refractory CD’ and were able to

return to a traditional gluten-free diet without return of symptoms [47].

Immune-modulating factors

The high frequency of individuals sensitised to a broad range of cereal (i.e. wheat)

proteins led to the suggestion that wheat (and related cereal) foods may have high

immunogenic potential, perhaps greater than other foods in general, although without

any occurrence of clinical symptoms [48]. We hypothesised that the consumption of

wheat positively influences the maturation of the immune system in early childhood in ‘cross-talking’ with the intestinal microbial community [49]. This may especially be

relevant in populations not yet affected by the ‘western lifestyle’ with its increased

hygiene [50], and not yet saddled with the related ‘western lifestyle syndrome’ characterised by disturbed immune and (intestinal) microbial functioning and

increased susceptibility to chronic inflammatory diseases. Western urban

environments often lack many of the microbes with which humans have co-evolved,

and which may function as inducers of immune-regulatory circuits [51,52]. Integration

of research on factors related to gut microbiota (including foetal programming by

maternal microbial exposure, neonatal programming and hygiene), on diet and lifestyle

factors, and on human genetics and epigenetics, will hopefully reveal some of the

immune-regulatory environmental factor(s) to explain the recent increase in immunerelated

diseases. Many studies have been conducted to identify the features of a ‘healthy microbiome/microbiota’ and the alterations on the host-microbiota cross-talk,

promoting the progress from health to disease in diverse disorders. These studies show

the enormous complexity and challenges of this scientific arena. Advances could open

ways to the development of microbiome-informed strategies for (personalised)

preventive and therapeutic measures including dietary strategies that help optimise the

partnership between the gut microbiota and host immunity, increasing microbiome

homeostasis in, and health resilience of, the host [53]. The manipulation of the gut

microflora is in its infancy but may have enormous potential for the future with regard

to prevention of immune system-mediated diseases [51,52]. How intestinal microbiota

may play a role in the development of the immune system was demonstrated during a

helminth therapy (through experimental hookworm infection), showing a significant increase in microbial species richness and, interestingly, a promoted tolerance in

coeliac subjects to escalating gluten challenges [54,55]. Helminth infections are known

to be correlated with a Th2 response [56]. In this regard, measurement of IgE or other

Th2 markers might be of interest to demonstrate a possible reversion of the immune

system away from autoimmunity (i.e. away from CD).

Health Grain Forum Intervention Study

The above refers to an increasing but still small percentage of the population. There

are currently solid grounds to advise the general consumer, i.e., the majority of the

population, to consume whole grain wheat products. Very large cohort studies clearly

demonstrate that consumption of whole grain products, including wheat and especially

the cereal bran fraction, significantly reduces the risk of several chronic diseases

[57,58]. These diseases are common, and therefore reducing these risks has a major

effect on life expectation and wellbeing. Nevertheless, worldwide, an anti-wheat and

anti-gluten hype has developed over the last five years, with significant impact on all

parts of the cereal supply chain and concomitantly significantly reduced sales of bread,

breakfast cereals and pasta products in various markets. The question arises why so

many people (≈30% in the USA, 15% in Australia, and increasing numbers in other

Western countries) seemingly feel more comfortable on a gluten-free or wheat-free

diet. Hard data about negative human health effects (beyond CD and wheat allergy)

are lacking, although popular books such as ‘Wheat Belly’ [59] and ‘Grain Brain’ [60]

suggest differently. In these books, the cereal supply chain is blamed for feeding the

world with sick-making food, but several of the arguments used are objectively wrong

[61,62]. The clinical picture of NCWGS is variable and usually includes IBS-like

gastrointestinal manifestations and neurological symptoms, such as foggy mind and

headache [15]. Expert criteria for the diagnosis of NCWGS have been recommended,

but specific and sensitive biomarkers for NCWGS are lacking [63]. Health Grain

Forum now proposes to perform a double-blind placebo-controlled human intervention

study addressing the effects of different wheat species, their components, and various

processing steps towards end products. This study aims at measuring effects on human

metabolism and health parameters to obtain reliable data useful for future human

dietary recommendations and appropriate food processing and product development.

In vivo effects, to be measured in this study, are related to gut feeling and adverse

effects, analysis of gut microbiota and colonic metabolism, and to gut permeability.

The intervention will also include the measurement of nocebo effects on the

consumer’s perception after consumption. The intervention will include a wellcontrolled

cohort of IBS patients. A consortium of research organisations and

stakeholder cereal food companies has recently been established. The project may start

in 2016 [64].

The societal context

Health care costs in The Netherlands (with 17 million inhabitants) amounted to almost

100 B€ in 2015, with an estimated annual increase of 6%, which is much higher than

the total Dutch economic growth. With this amount, the Dutch spend per capita almost

as much as a citizen of the USA, which is the highest in the world. The spectacular rise

of these costs is partly due to an increasing elderly population, to increasing prices of

special medical treatments in health care, and last but not least to the enormous

increases in the prices and in the applications of medicines. In this regard, the

pharmaceutical industry plays a dubious role [65]. Remarkably, in Cuba, the health

care budget per capita is 20 times lower compared to the USA, however, with an equal

life expectation. People have argued that part of the health care budget should be bent

towards the development, testing and promotion of efficient prevention measures. We,

therefore, argue that also ‘big food industries’ should take a responsibility for the

health status of the population.

Conclusion

The societal context demonstrating increasing costs for health care should strongly

urge national governments to reconsider their health care policies and change these

into disease prevention policies with a focus on the maintenance of the health of its

individual people. In this paper, we give a variety of examples for plant and foodtechnological

related strategies that may contribute as small steps towards the

reduction of the incidence of remarkable food-induced syndromes, specifically CD and

NCWGS, caused by the consumption of one of our oldest and most frequently

consumed foodstuffs worldwide.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the EU 7th Framework Programme project ‘Traditional

Food Network to improve the transfer of knowledge for innovation’ (TraFooN) (grant

agreement no: 613912) that partially supported writing of this paper.

References

1. Strait SG. Tooth use and the physical properties of food. Evol Anthropol 1997; 5:

199-211.

2. Sponheimer M, Lee-Thorpe JA. Isotopic evidence for the diet of an early hominid,

Australopithecus africanus. Science 1999; 283: 368-370.

3. Senut B, Pickford M, Gommery D, et al. First hominid from the Miocene

(Lukeino formation, Kenia). Compt Rend Acad Sci Series IIA 2001; 332: 137-144.

4. Cerling TE, Manthi FK, Mbua, et al. Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of

Turkana Basin hominins. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2013; 110: 10501-10506.

5. Kuhlwilm M, Gronau I, Hubisz MJ, et al. Ancient gene flow from early modern

humans into Eastern Neanderthals. Nature 2016; doi:10.1038/nature16544.

6. Henry AG, Brooks AS, Piperno DR. Microfossils in calculus demonstrate

consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq;

Spy I and II, Belgium). Proc Natl Acad Sci 2011; 108: 486-491.

7. Lippi MM, Foggi B, Aranguren B, et al. Multistep food plant processing at Grotta

Paglicci (Southern Italy) around 32,600 cal B.P. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015; 112:

12075-12080.

8. Eitam D, Kislev M, Karty A, et al. Experimental barley flour production in

12,500-year-old rock-cut mortars in Southwestern Asia. PLoS ONE 2015;

10:e0133306. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133306.

9. Kislev ME, Weiss E, Hartmann A. Impetus for sowing and the beginning of

agriculture: ground collecting of wild cereals. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015; 101:

2692-2695.

10. Miedaner T, Longin F. Unterschätzte Getreidearten Einkorn, Emmer, Dinkel& Co. AgriMedia GmbH & Co. KG, 2012; ISBN 978-3-86263-079-0.

11. Guandalini S. Historical perspective of celiac disease. In: Fasano A, Troncone R,

Branski D (eds): Frontiers in Celiac Disease. Pediatr Adolesc Med. Basel, Karger,

2008; 12: 1-11.

12. Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in

undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 88-93.

13. Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Lancet 1978; 1: 1358-1359.

14. Wray D. Gluten-sensitive recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Digestive Diseases and

Sciences 1981; 26: 737-740.

15. Catassi C. Gluten sensitivity. Ann Nutr Metab 2015; 67 (suppl 2): 16-26.

16. The NPD Group/Dieting Monitor. 200 million restaurant visits include a glutenfree

order. www.ndp.com.

17. Gilissen LJWJ, Van der Meer IM, Smulders MJM. Reducing the incidence of

allergy and intolerance to cereals. J Cereal Sci 2014; 59: 337-353

18. Smulders MJM, Jouanin A, Schaart J, et al. Development of wheat varieties with

reduced contents of coeliac-immunogenic epitopes through conventional and GM

strategies. In: Koehler P (ed): Proceedings of the 28th Meeting, Working Group on

Prolamin Analysis and Toxicity. Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für

Lebensmittelchemie, Freising, 2015; pp. 47-56.

19. Kissing Kucek L, Veenstra LD, Ammuaycheewa P, et al. A grounded guide to

gluten: How modern genotypes and processing impact wheat sensitivity. Compr

Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2015; doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12129.

20. Van den Broeck HC, De Jong HC, Salentijn EMJ, et al. Presence of celiac disease

epitopes in modern and old hexaploid wheat varieties: wheat breeding may have

contributed to increase prevalence of celiac disease. Theor Appl Genet 2010; 121:

1527-1539.

21. Van den Broeck HC, Chen H, Lacaze X, et al. In search of tetraploid wheat

accessions reduced in celiac disease-related gluten epitopes. Mol Biosyst 2010; 6:

2206-2213.

22. Van den Broeck HC, Cordewener JHG, Nessen MA, et al. Label free targeted

detection and quantification of celiac disease immunogenic epitopes by mass

spectrometry. J Chromatography A 2015; 1391: 50-71.

23. Tanner GJ, Blundell MJ, Colgrave ML, et al. Creation of the first ultra-low gluten

barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) for coeliac and gluten-intolerant populations. Plant

Biotechnol J 2015; doi: 10.1111/pbi.12482

24. Van Herpen TWJM, Goryunova S, Van der Schoot J, et al. Alpha-gliadin genes

from the A, B and D genomes of wheat contain different sets of celiac disease

epitopes. BMC Genomics 7: 1.

25. Van den Broeck HC, Gilissen LJWJ, Smulders MJM, et al. Dough quality of bread

wheat lacking alpha-gliadins with celiac disease epitopes and addition of celiacsafe

avenins to improve dough quality. J Cereal Sci 2011; 53: 206-216.

26. Becker D, Wieser H, Koehler P, et al. Protein composition and techno-functional

properties of transgenic wheat with reduced alpha-gliadin content obtained by

RNA interference. J Appl Bot Food Qual 2012; 85: 23-33.

27. Gil-Humanes J, Pistón F, Tollefsen S, et al. Effective shutdown in the expression

of celiac disease-related wheat gliadin T-cell epitopes by RNA interference. Proc

Natl Acad Sci 2010; 107: 17023-17028.

28. Pistón f, Gil-Humanes J, Rodriguez-Quijano M, et al. Down-regulating gammagliadins

in bread wheat leads to non-specific increase in other gluten proteins and

has no major effect on dough gluten strength. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e24754.

29. Gil-Humanes J, Pistón F, Giménez MJ, et al. The introgression of RNAi silencing

of gamma-gliadins into commercial lines of bread wheat changes the mixing and

technological properties of the dough. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e45937.

30. Gil-Humanes J, Pistón F, Altamirano-Fortoul R, et al. Reduced-gliadin wheat

bread: an alternative to the gluten-free diet for consumers suffering gluten-related

pathologies. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e90898.

31. Barro F, Iehisa JCM, Giménez MJ, et al. Targeting of prolamins by RNAi in bread

wheat: effectiveness of seven silencing-fragment combinations for obtaining lines

devoid of coeliac disease epitopes from highly immunogenic gliadins. Plant

Biotech J 2016; 14: 986-996.

32. Wen S, Wen N, Pang J, et al. Structural genes of wheat and barley 5-

methylcytosine DNA glycosylases and their potential applications for human

health. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012; 109: 20543-20548.

33. Kasarda DD. Can an increase in celiac disease be attributed to an increase in the

gluten content of wheat as a consequence of wheat breeding? J Agric Food Chem

2013; 61: 1155-1159.

34. Gilissen LJWJ, Van den Broeck HC, Londono DM, et al. Food-related strategies

towards reduction of gluten intolerance and gluten sensitivity. In: Koehler P (ed):

Proceedings of the 25th Meeting, Working Group on Prolamin Analysis and

Toxicity. Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Lebensmittelchemie, Freising, 2012; pp.

29-35.

35. Bassi S, Maningat CC, Chinaswamy R, et al. Alcohol-free wet extraction of gluten

dough into gliadin and glutenin. United States Patent, No 5,610,277.

36. Kratzer W, Kibele M, Porzner M, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in Germany:

A prospective follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 2612-2620.

37. Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in

Europe: Results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med

2010; 42: 587-595.

38. Laass MW, Schmitz R, Uhlig HH, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in

children and adolescents in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015; 112: 553-560.

39. Loponen J. Prolamin degradation in sourdoughs. Academic Dissertation. EKT

series 1372. University of Helsinki.

40. Greco L, Gobbetti M, Auricchio R, et al. Safety for patients with celiac disease of

baked goods made of wheat flour hydrolysed during food processing. Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 24-29.

41. Stenman SM, Lindfors K, Venäläinen, et al. Degradation of coeliac diseaseinducing

rye secalin by germinating cereal enzymes: diminishing toxic effects in

intestinal elipthelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2010; 161: 242-249.

42. Schwalb T, Wieser H, Koehler P. Studies on the gluten-specific peptidase activity

of germinated grains from different cereal species and cultivars. Eur Food Res

Technol 2012; 235: 1161-1170.

43. Loponen J, Sontag-Strohm T, Venäläinen, et al. Prolamin hydrolysis in wheat

sourdoughs with differing proteolytic activities. J Agric Food Chem 2007; 55:

978-984.

44. Loponen J, Kanerva P, Zhang C, et al. Prolamin hydrolysis and pentosan

solubilization in germinated-rye sourdoughs determined by chromatographic and

immunological methods. J Agric Food Chem 2009; 57: 746-753.

45. Vader W, Kooy Y, Van Veelen P, et al. The gluten response in children with

celiac disease is directed towards multiple gliadin and glutenin peptides.

Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 1729-1737.

46. Camarca A, Anderson RP, Mamone G, et al. Intestinal T cell responses to gluten

peptides are largely heterogeneous: Implications for a peptide-based therapy in

celiac disease. J Immunol 2009; 182: 4158-4166.

47. Hollon J, Puppa EL, Greenwald B, et al. Effect of gliadin on permeability of

intestinal biopsy explants from celiac disease patients and patients with non-celiac

gluten sensitivity. Nutrients 2015; 7: 1565-1576.

48. Zuidmeer L, Goldhahn K, Rona RJ, et al. The prevalence of plant food allergies:

A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 121: 1210-1218.

49. Gilissen LJWJ, Van der Meer IM, Smulders MJM. Reducing the incidence of

allergy and intolerance to cereals. J Cereal Sci 2014; 59: 337-353.

50. Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, Van Ree R. Allergy, parasites and the hygiene

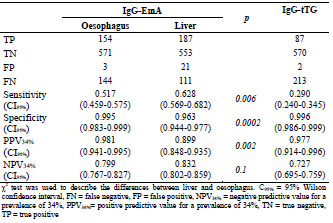

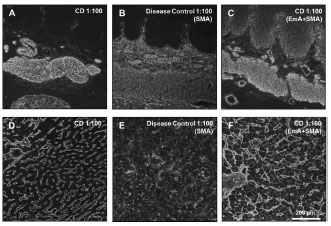

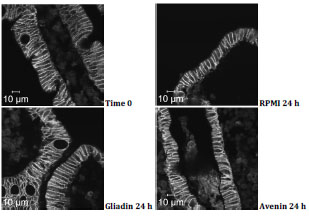

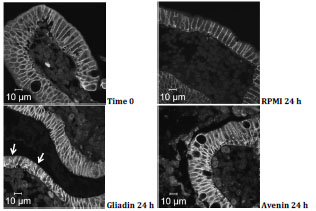

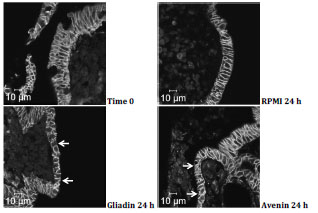

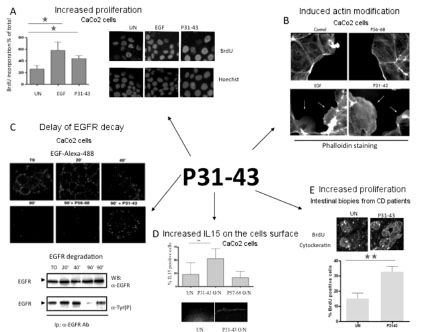

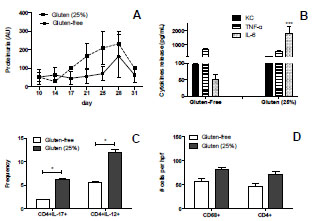

hypothesis. Science 2002; 296: 490-494.